In this article

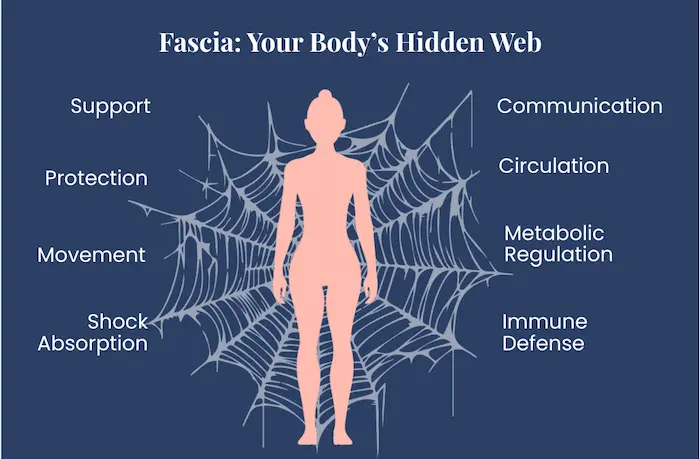

What is fascia? It can be helpful to imagine your body as a giant, living spiderweb. Every muscle, organ, and bone is connected by delicate, yet incredibly strong threads that hold everything together—and help you move, bend, and even heal. These threads aren’t silk or fiber you can see on the surface; they’re your fascia, and they’re one of the most overlooked but essential parts of your health. Think of fascia as the body’s “shock absorber,” “support network,” and even a secret messenger system – all rolled into one.

Fascia isn’t just about flexibility or soreness after a workout. It plays a pivotal role in your overall well-being—from helping your organs stay in place to affecting your circulation, hormone signaling, and immune function. Emerging research shows that fascia may even have a hand in autoimmune conditions like Hashimoto's thyroiditis, where your body’s immune system mistakenly attacks your thyroid, leading to hypothyroidism. But the influence of fascia doesn’t stop there—it’s also linked to hormone shifts during perimenopause and menopause, digestive health, and even your ability to lose weight!

So, whether you’re struggling with thyroid issues, gut problems, stubborn weight, or the aches and pains that seem to come with age, understanding fascia could be a game-changer. In this article, we’ll explore what fascia is, why it’s crucial to your health, how it connects to conditions like Hashimoto’s and hypothyroidism, and the many ways you can support and resolve fascia problems—from medical interventions to physical therapies, complementary treatments, nutrition, and beyond. Get ready to meet the “hidden web” inside your body that could unlock a whole new level of health.

Fascia might not be something you think about every day, but it’s one of the most essential parts of your body. Imagine a continuous, three-dimensional web of connective tissue made mostly of collagen, wrapping around every muscle, bone, nerve, blood vessel, and organ. This intricate network supports your body, allows smooth movement, cushions your organs, and even helps tissues “talk” to each other. Far from being just filler, fascia is also rich in sensory nerves, helping your body sense position, movement, and even pain.

Healthy fascia is flexible, hydrated, and elastic, moving effortlessly with your body. But when it becomes stiff, dehydrated, or develops adhesions, it can cause pain, limit mobility, and trigger chronic inflammation. Fascia doesn’t just support your muscles—it also helps regulate blood flow, influence immune responses, and even plays a role in healing.

In short, fascia is much more than a passive structure. It’s a dynamic, responsive network that impacts your movement, your body’s communication systems, and your overall health. Caring for your fascia—through movement, hydration, and mindful therapies—can help you feel more flexible, reduce pain, and support long-term wellness.

Autoimmune diseases — where the body’s own immune system mistakenly attacks its own tissues — are most often thought of in terms of “organs under attack.” But increasingly, scientists are realizing that the body’s connective-tissue network — the fascia — may also be deeply involved. The fascia isn’t just passive scaffolding: it’s a living tissue, rich in fibroblasts, immune cells, extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, nerves, and blood vessels, forming a dynamic interface between structure, movement, and immunity.

That means when autoimmunity hits — for example, in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, an autoimmune attack on your thyroid — fascia may not be spared. Growing clinical and cellular evidence suggests that in some individuals, autoimmune thyroid disease and fascial inflammation may share underlying immunological pathways and contribute to symptoms beyond your thyroid gland itself.

- There are documented instances where an autoimmune disease of the fascia — Eosinophilic fasciitis (EF) — appears alongside autoimmune thyroid disease. One case series published in 2005 described a patient with EF in the setting of autoimmune thyroiditis.

- Going further back, a series of 3 patients from 1980 diagnosed with EF all had concurrent thyroid disease — two with Hashimoto’s, one with Graves’ disease.

- A 2024 review of fascia’s physiological roles emphasizes that fascia is intimately involved in immune surveillance and organ inflammation.

These associations don’t prove that Hashimoto’s causes fascial disease, or vice versa. But they do raise a strong possibility that for some people, thyroid autoimmunity and fascial pathology may coexist, overlap, or influence one another.

To understand how thyroid autoimmunity could intersect with diseases of the fascia, it helps to look at what we know from immunology, cell biology, and connective tissue research:

- In Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, a leading mechanism of thyroid-cell destruction involves the Fas–Fas ligand pathway (Fas/FasL). Thyroid follicular (thyrocyte) cells express Fas, and when Fas engages with FasL — a “death signal” — those thyroid cells undergo programmed cell death (apoptosis). This process has been widely documented in Hashimoto’s.

- Meanwhile, fascia fibroblasts — the cells that build and maintain fascia — are not inactive. They also play active roles in tissue repair, immunomodulation, and inflammation. In fact, fascia fibroblasts contribute immune-related signals and help coordinate inflammatory and fibrotic responses.

- In inflammatory or fibrosing diseases of fascia (like EF, or potentially other under-recognized fascial-immune disorders), the protein scaffolding of fascia can become altered, with increased collagen deposition, thickening, reduced elasticity, immune cell infiltration, and fibrosis.

- Because the immune system and connective-tissue cells (like fibroblasts) communicate closely, autoimmunity could plausibly trigger or worsen changes to the fascia, leading to stiffness, muscle weakness, chronic pain, and reduced mobility. This fits with emerging conceptual models that describe fascia as a “regulator tissue” for immune, neural, and structural balance.

In short: the same immune dysregulation that damages thyroid cells may — in some people — also affect fibroblasts and fascia.

The implications of fascia’s involvement in autoimmune conditions and thyroid dysfunction, like Hashimoto’s, are potentially broad:

- This may help explain symptoms that often go unexplained in thyroid patients — chronic muscle and joint pain, stiffness, “frozen” fascia or tightness, poor mobility, or fibromyalgia-like symptoms — even when thyroid labs are “optimized.”

- Treating thyroid autoimmunity alone may not be sufficient. We might also need to consider fascial health and inflammation to relieve symptoms.

- Recognizing fascia as an immunologically active tissue may open new therapeutic avenues — for example, combining endocrine care with physical therapies, anti-inflammatory strategies, and connective tissue support.

- For researchers, this suggests a fruitful (but still under-explored) frontier: better understanding how immune dysregulation affects fascia, how fascia contributes to systemic symptoms, and whether interventions targeting fascia can benefit people with autoimmune disorders.

Not everyone with an autoimmune thyroid condition will ever develop fascial symptoms or disease. And the presence of autoimmune antibodies, immune cell dysfunction, or thyroid-specific autoimmunity doesn’t guarantee that fascia will be affected.

It’s also important to stress that the science is still very limited. Most of the strong data on the fascia’s role in autoimmunity comes from basic research, animal models, or case reports. Large-scale human studies directly showing that autoimmune thyroid disease causes clinically significant fascial disease are lacking. Many of the associations remain rare, anecdotal, and can’t be generalized to all patients.

Living with hypothyroidism isn’t just about a slower metabolism or fatigue — it can quietly undermine the very scaffolding that supports your body: the fascia, tendons, skin, and connective tissue matrix. When thyroid hormone levels drop, the cells responsible for maintaining connective tissue also slow down their normal work. Collagen turnover and extracellular matrix remodeling (ECM) – the way connective tissue continually rebuilds and reorganizes itself – begin to falter. The result? Fascia and connective tissues that become thicker, less flexible, and more rigid — symptoms that may silently build until you start noticing stiffness, muscle tension, aches, and restricted mobility -- sometimes known as hypothyroid myopathy or Hoffmann's syndrome.

Laboratory research shows that thyroid hormones such as triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) directly influence connective tissue. Laboratory studies with human cells show that when exposed to thyroid hormones (especially in combination with ascorbic acid), cells significantly increase the production of collagen and other components. This suggests that normal thyroid hormone levels help maintain healthy collagen production and turnover processes crucial for tissue elasticity, resilience, and repair.

In states of hypothyroidism, with low thyroid hormone levels and elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone, there is evidence from animal studies that connective tissues accumulate abnormally high levels of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) and collagen in certain organs.

There are other classic signs of connective tissue changes in hypothyroidism that reflect impaired collagen and ECM, including dry, rough skin, slower tissue turnover, and reduced elasticity.

Taken together, these data suggest that thyroid hormones are not only critical for metabolism — they also act as key regulators of the structural proteins and matrix components that keep fascia, tendons, muscle groups, skin, and connective tissue supple and functional.

When connective tissue remodeling slows or becomes dysregulated due to hypothyroidism, the physical consequences can be substantial:

- Many people with hypothyroidism experience muscle aches, stiffness, and joint pain, especially in hands, knees, and other weight-bearing joints.

- A well-recognized condition, hypothyroid myopathy, affects a substantial portion of people with untreated or poorly managed thyroid dysfunction. Estimates range from around 30% to 80%. Symptoms of hypothyroid myopathy include muscle weakness, pain, stiffness, delayed muscle relaxation, and reduced muscle endurance.

- Studies of hypothyroid myopathy often reveal increased connective tissue within muscle tissue — meaning more ECM and less healthy muscle fibers, which can lead to stiffness or a “doughy” feeling in muscles and surrounding tissues.

- Because fascia and connective tissues are integral to how muscles, tendons, and joints glide and move together, when fascia is less elastic or more rigid, that likely contributes to reduced mobility, slower recovery from strain, increased susceptibility to chronic pain, and possibly myofascial pain syndromes.

Hypothyroidism can also make fascia and nerves more vulnerable. Problems like plantar fasciitis, carpal tunnel syndrome, tarsal tunnel syndrome, and frozen shoulder (adhesive capsulitis) tend to show up more often in people with an underactive thyroid. Extra fluid and glycosaminoglycan buildup in soft tissues, weight gain and altered mechanics, and low-grade inflammation all seem to stiffen fascia and crowd nerve tunnels in the hands, feet, and shoulders.

The journey from perimenopause into menopause isn’t just about skipping periods or hot flashes — it can also quietly transform your body’s connective tissues. As estrogen levels plunge, so does a critical support system inside you: the integrity and elasticity of fascia, tendons, ligaments, and other connective tissue structures. This shift has real consequences for how your body moves, feels, and recovers.

- Researchers have discovered that fascial fibroblasts — the cells that build and maintain fascia — carry estrogen receptors (and also receptors for the hormone relaxin).

- In laboratory experiments, when human fascial cells were exposed to varying levels of estradiol (the primary form of estrogen), they significantly changed how they built the ECM. With higher estrogen, the production of collagen I drops, while levels of collagen III and fibrillin — components associated with elasticity — increased.

- Under low estrogen conditions, like in menopause, the balance flips: collagen I becomes more dominant, while collagen III and fibrillin decline — driving tissue toward rigidity rather than flexibility.

This means that as estrogen declines, fascia and other connective tissues may become thicker, stiffer, and less able to stretch or glide. The subtle “give” in ligaments, fascia, and tendons — that allows smooth movement — starts to fade.

This hormonal-driven remodeling of connective tissue helps explain why many women — even those without obvious arthritis — start experiencing musculoskeletal complaints around midlife.

- Joint and tendon stiffness or pain become more common. Clinical reviews note that estrogen helps maintain the collagen content and structural properties of tendons and ligaments; when estrogen levels fall, these tissues are more prone to stiffness and degeneration.

- Pelvic connective tissue shows marked structural changes after menopause (e.g., a 75% drop in collagen I in postmenopausal women not on hormones) compared with pre-menopausal counterparts.

- Your skin is another form of connective tissue, and menopause is strongly associated with collagen atrophy. Decreased collagen can reduce skin elasticity, increase fragility, slow wound healing, and increase dryness and thinning. (PubMed)

- Because fascia and connective tissue are interwoven with muscles, tendons, and joints, these changes may also underlie myofascial pain, trigger points, reduced mobility, and general musculoskeletal discomfort. This may explain why many perimenopausal and menopausal women report new or worsening aches, tightness, back pain, pelvic discomfort, or fibromyalgia-like symptoms even in the absence of arthritis or injury.

Not every woman in perimenopause or menopause will feel dramatic tissue stiffness or pain — a lot depends on other factors: genetics, lifestyle, previous injuries, physical activity levels, weight-bearing or movement habits, and whether she’s using hormone therapy (or at what dose). But because fascia expresses hormone receptors, the drop in estrogen is a biologically plausible mechanism for many of the seemingly “mysterious” menopausal symptoms: the aches, stiffness, heaviness, decreased flexibility — even in the absence of classic arthritis or bone disease.

Because fascia is a dynamic, living network that envelops and supports your internal organs, including the gut, what happens in your gastrointestinal system and in your microbiome can affect your fascia—and vice versa.

- Your fascia is full of nerves and blood vessels and is deeply linked to your body’s lymphatic and immune systems. Some experts describe fascia as a kind of “master communicator,” able to sense and relay changes across the body — including from internal organs to the nervous system.

- Because fascia surrounds the abdominal cavity and organs, physical tension, adhesions, or restrictions in abdominal/visceral fascia could mechanically influence the position, mobility, or tension of the gut and its nerve supply. Practitioners working with fascial release frequently report improvements in digestion, bloating, cramping, and gut-related discomfort after abdominal or visceral fascial work.

- On the flip side: the gut microbiome — via its profound effects on immunity, inflammation, and gut barrier integrity — appears to influence systemic tissue health, including musculoskeletal and connective tissue systems—for example, emerging research on the gut microbiome’s influence on musculoskeletal injury and recovery.

- When your gut barrier is compromised (“leaky gut”), microbes or pro-inflammatory molecules may pass into your bloodstream, triggering systemic low-grade inflammation. Inflammation can affect tissues such as fascia, muscles, tendons, and joints. This link between gut permeability, microbiota, and musculoskeletal tissue health has been observed as a factor in slower healing after injuries or increased likelihood of musculoskeletal pain.

- In functional gut disorders like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), altered gut microbiome and increased gut permeability often go hand in hand with heightened visceral sensitivity and dysregulated gut-brain signaling.

It also works the other way around — fascial restriction or imbalance can compromise gut function:

- Tight or restricted fascia in the abdomen, pelvis, or trunk can compress or distort the gut’s anatomical positioning, potentially altering motility, organ alignment, blood flow, or nerve signaling. Many practitioners believe this can contribute to symptoms like constipation, bloating, or visceral discomfort.

- Through its nerve-rich and fluid-transporting nature, healthy fascia may facilitate proper circulation, lymphatic flow, and even autonomic regulation — all of which support healthy digestion and organ function.

Fascia plays an active role in how our bodies move, how energy is stored and used, and even how fat and fluid are distributed. Because of that, the condition of your fascia may affect not only how you move, but also how well you can lose weight — and keep it off.

- With metabolic stress (obesity, insulin resistance, poor glucose control), fascia can remodel — often in maladaptive ways. In conditions such as obesity or type 2 diabetes, research shows that fascia (and associated connective tissues) sometimes become thicker or stiffer, with altered mechanical properties.

- That remodeling can impair how muscle and fat tissues behave. When fascia becomes fibrotic or dense, it may hinder the “sliding and gliding” that supports healthy movement, force transmission, and flexibility, and may also interfere with microvascular flow and lymphatic drainage — both important for nutrient delivery, waste removal, and fat metabolism.

Fascia quality can influence how effectively your muscles work, how fat is deposited or mobilized, and how efficiently your body handles metabolic processes — all of which play a role in fat loss, weight management, and body composition. When fascia becomes compromised — through chronic inflammation, poor movement/ inactivity, metabolic stress, or localized tissue changes — several things can go wrong:

- Reduced muscle efficiency and mobility. Dense or stiff fascia decreases flexibility and range of motion, limiting what you can do in exercise or daily movement. That reduces your ability to burn calories, build lean muscle, or engage in strength training — all key for sustainable weight loss and metabolic health.

- Altered fat tissue behavior. According to recent research, in obesity and metabolic disease, the fascia around muscles can undergo “fibro-adipogenic remodeling” — meaning connective tissue fibroblasts and progenitor cells shift toward the formation of fat cells, impairing metabolism.

- Impaired circulation and lymphatic flow. Fascia helps regulate lymphatic flow, nutrient and fluid distribution, and waste removal. When fascia becomes stiff or fibrotic, these functions may be degraded — potentially leading to fluid retention, poor waste clearance, slowed metabolic activity, and reduced fat mobilization.

- Greater risk of fibrosis and tissue rigidity. Chronic excess fat, metabolic stress, or inactivity can promote extracellular matrix (ECM) overdeposition: more collagen and fibrotic tissue, less elasticity. That makes fascia—and the tissues it supports—less adaptable, less mobile, and more prone to dysfunction.

In general, if fascia becomes unhealthy (stiff, dense, fibrotic), it may blunt the benefits of diet, exercise, and other weight-loss efforts, slowing fat loss, making it less efficient, or increasing the likelihood of rebound.

It’s empowering and important to realize that your symptoms are not “in your head!” There is a clear biological mechanism linking autoimmunity, thyroid hormone deficiency, menopausal changes, gut health, and the ability to lose weight to structural tissue changes in your body. Recognizing this can shape more effective strategies for your well-being.

Fascia is remarkably adaptable, and with the right combination of medical, physical, movement-based, nutritional, and lifestyle strategies, it can be restored to flexibility, glide, and resilience. Let’s look at the approaches to help resolve fascia-related issues.

Optimize your thyroid treatment

Since thyroid hormones help regulate ECM production in tendons, fascia, and connective tissue, optimal hormone replacement therapy may help restore healthier collagen and matrix dynamics, potentially alleviating or preventing structural issues and stiffness related to fascia.

Consider HRT

Research suggests that for women in perimenopause or menopause, bioidentical hormone replacement therapy or other hormone-balancing interventions can help preserve collagen synthesis and fascia elasticity, reducing tissue stiffness and associated discomfort.

Support gut health

A balanced gut microbiome, good gut barrier integrity, an anti-inflammatory diet, and avoidance of chronic gut dysbiosis may reduce systemic inflammation — potentially benefiting your fascia and connective tissues.

Myofascial release therapy

When fascia is “stuck” — dehydrated, inflamed, or restricted — this may impair gut-organ mobility, disturb gut-brain signaling, or impair nutrient, fluid, or waste exchange. Techniques like Rolfing, structural integration, or targeted myofascial release apply controlled pressure and movement to fascial restrictions, restoring tissue glide and elasticity. These therapies can reduce musculoskeletal pain, improve range of motion, and positively influence the ECM in fascia.

Physical and manual therapy

Stretching, strengthening, and posture-focused interventions enhance fascial alignment and function. Research indicates that combining strength and flexibility exercises improves fascia and joint mechanics, reducing the risk of injury. Other manual therapies, such as massage, manual lymphatic drainage, or connective tissue manipulation, can reduce subcutaneous fat thickness and regional fat deposits (especially in cellulite-prone areas) when combined with healthy lifestyle practices.

If you’re interested in getting started on your own, here's an excellent 30-minute video featuring a fascia-stretching class from Erin Tietz of Daily Fascia.

Dry needling, trigger point injections, and acupuncture

Dry needling, trigger point injections, and acupuncture modulate neuromuscular activity, help relax fascial tightness, and decrease pain. Evidence suggests these interventions influence connective tissue remodeling and local blood flow, contributing to improved tissue function.

Immunosuppressive therapy

For conditions such as eosinophilic fasciitis or autoimmune-related fascial inflammation, immunosuppressive therapy, including corticosteroids, may be needed to reduce fibrosis and prevent permanent tissue damage.

Movement-based approaches

Slow, mindful movements and stretches found in practices like yoga, pilates, tai chi, and stretching can enhance fascial hydration and elasticity, supporting tissue glide while improving posture and balance. Research indicates that yoga and similar practices can modulate fascial tension, reduce stiffness, and improve musculoskeletal function.

Breathwork

Focused breathing techniques improve oxygen delivery to tissues and support fascial relaxation by modulating the autonomic nervous system activity.

Hydrotherapy

Contrast baths, warm water immersion, fascial hydrotherapy, or aquatic exercise enhance circulation, reduce fascial stiffness, and support connective tissue recovery. Water-based therapies also facilitate gentle movement, which encourages fascia elasticity.

Hydration

Adequate water intake is essential for the fascia’s elastic properties and tissue glide. Dehydration leads to stiffened fascia and impaired extracellular matrix function.

Collagen support

Foods and supplements rich in collagen, vitamin C, and glycine support connective tissue repair and collagen synthesis, contributing to fascia elasticity.

Anti-inflammatory diet

Foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants from fruits and vegetables, and plant polyphenols help reduce chronic fascial inflammation and oxidative stress, supporting healthy connective tissue.

Nutritional supplements

- Collagen peptides give the body the building blocks it needs to repair and maintain fascia and other connective tissues

- Vitamin C helps the body make strong collagen fibers

- Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM)supports elastic, “non-sloppy” fascia

- Hyaluronic acid helps fascia stay hydrated and slippery, so layers can glide instead of sticking

- Omega-3 supplements like fish oil, as well as flax, chia, and curcumin, can calm low-grade inflammation that contributes to painful, “sticky” fascia

- Magnesium helps muscles and fascia relax and may ease myofascial tightness and trigger point pain

At Paloma, we’ve learned something important: your fascia—this incredible web of connective tissue wrapped around every organ, muscle, and system—plays a far bigger role in your health than most people realize. Yet in most traditional treatment plans, fascia barely gets a mention. The focus is usually on adjusting thyroid medication, prescribing hormone therapy, or telling people to simply “eat less and move more” when weight becomes a struggle.

But fascia connects everything: your thyroid gland, your immune system, your gut, your hormones, your metabolism, and even how fluid moves through your body. When fascia becomes stiff, inflamed, or dehydrated, it can worsen symptoms of Hashimoto’s, hypothyroidism, perimenopause, menopause, and chronic gut issues—and it can make hormonal weight gain even harder to manage.

Science now shows that fascia isn’t just structural; it’s biologically active, immune-responsive, and deeply intertwined with autoimmune activity, inflammation, pain, and metabolic health. That means supporting your fascia can help improve mobility, reduce pain, enhance circulation, support digestion, support lymphatic flow, and make your whole system more responsive to hormonal and thyroid treatments.

That’s why at Paloma, our approach goes beyond prescriptions. We believe true healing comes from caring for the whole body ecosystem. Supporting fascia health may mean combining medical care, hormone balance, gut-healing strategies, targeted nutrition, hydration, gentle movement, breathwork, and hands-on therapies that improve tissue glide and elasticity.

Your fascia responds to care—and when it’s healthy, everything else works better. Paloma focuses on treating Hashimoto’s, hypothyroidism, perimenopause, menopause, gut health, and hormonal weight challenges in a holistic, integrative way. Paloma’s approach sees the whole you, honors the interconnectedness of your systems, and helps you feel strong so you can feel and live well in your body again!

- Fascia is a dynamic connective tissue network that influences movement, immunity, hormone signaling, circulation, digestion, and metabolic health.

- Autoimmune diseases like Hashimoto’s and the resulting hypothyroidism can alter fascia through immune pathways and reduced thyroid hormones, leading to stiffness, inflammation, and connective tissue dysfunction.

- Estrogen decline in perimenopause and menopause makes fascia thicker and less elastic, contributing to joint pain, stiffness, and decreased mobility.

- Gut health and fascia are deeply interconnected—gut inflammation can stiffen fascia, while fascial restrictions can impair digestion and gut–brain communication.

- Unhealthy fascia may slow weight loss by reducing muscle efficiency, impairing lymphatic flow, and altering fat tissue behavior.

- Fascial health can be improved through a combination of thyroid optimization, hormone therapy, gut-balancing strategies, myofascial release, movement-based therapies, and nutritional support.

.webp)