In this article

When it comes to eating for better health, the advice can feel endlessly confusing. One expert says to load up on plants, another emphasizes protein, and nearly everyone claims their approach is the answer for inflammation, weight, and long-term wellness. Two of the most talked-about frameworks today—the Real Food Pyramid, announced in early 2026, and Dr. Andrew Weil’s Anti-Inflammatory Pyramid, released in 2025—share common ground but differ in meaningful ways. If you’re living with Hashimoto’s or hypothyroidism, those differences matter. Understanding how each pyramid approaches protein, grains, fats, and supplements can help you make smarter, more personalized food choices that support stable blood sugar, reduced inflammation, and better thyroid function—without feeling overwhelmed or restricted.

In January 2026, the USDA unveiled the new “Eat Real Food” Pyramid, a reimagining of American dietary guidance that flips decades of nutrition advice on its head by placing whole, nutrient-dense foods squarely at the center of every plate. Responding to alarming rates of chronic disease—50% of Americans with prediabetes or diabetes, 75% of adults facing at least one chronic condition, and 90% of healthcare spending tied to preventable illnesses linked mainly to diet—this new framework explicitly calls out the dangers of highly processed foods that have dominated prior recommendations.

The new Real Food Pyramid is built on three main tiers: “Protein, Dairy & Healthy Fats,” “Vegetables & Fruits,” and “Whole Grains,” with a unifying message to “Eat Real Food.” The core idea is that better health starts with whole, naturally occurring foods rather than relying on medications to manage diet-driven chronic disease.

Key features of the Real Food Pyramid include:

- Prioritizing high-quality, nutrient-dense proteins from both animal and plant sources at every meal, accompanied by healthy fats from eggs, seafood, meat, full-fat dairy, nuts, seeds, healthy cooking oils, olives, and avocados.

- Emphasizing a wide variety of colorful, minimally processed vegetables and fruits in their original form, targeting roughly 3 servings of vegetables and 2 servings of fruit daily.

- Encouraging fiber-rich whole grains while discouraging refined carbohydrates and highly processed refined-grain products, with a general target of 2 to 4 whole-grain servings per day.

The guidelines highlight the burden of chronic disease—high rates of diabetes, prediabetes, and other long-term conditions—and explicitly link much of this to diet and lifestyle, arguing that decades of guidance tolerated or even promoted highly processed foods.

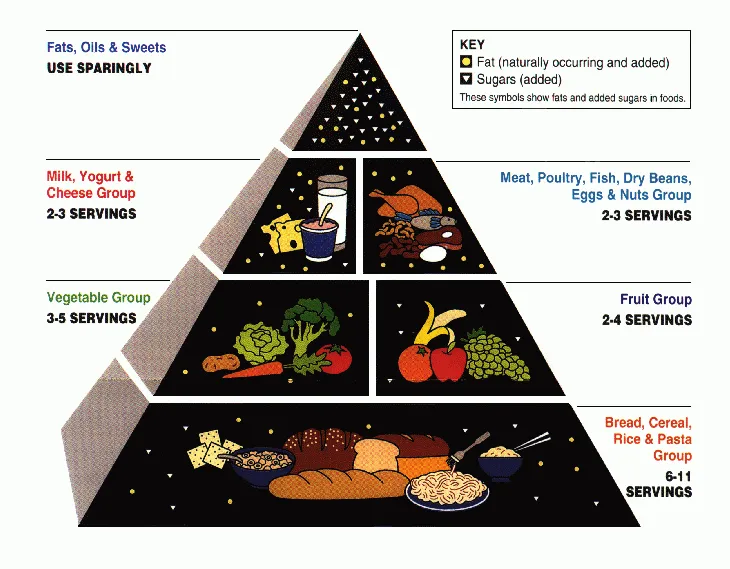

The 1992 Food Guide Pyramid, unveiled by the USDA as the first major visual tool for American eating habits, was designed to translate complex nutrition science into an easy, tiered structure that mimicked a pyramid—encouraging people to “eat more from the bottom and less from the top.” At its broad base sat grains (bread, cereal, rice, and pasta), with a recommended 6 to 11 servings per day, reflecting the era’s heavy emphasis on carbohydrates as the foundation of energy and health. This category often included refined options like white bread and sugary cereals, with little distinction in quality. Above grains came fruits (2-4 servings) and vegetables (3-5 servings) in slimmer tiers, acknowledging their nutrient density but positioning them secondary to carbs, followed by a narrower band for dairy (2-3 servings) and proteins like meat, poultry, fish, eggs, beans, and nuts (2-3 servings), all intended to guide daily intake based on a 2,000-calorie diet for average adults.

The pyramid’s top pinnacle featured fats, oils, and sweets, marked with a “use sparingly” directive, aiming to curb overconsumption of calorie-dense items amid rising concerns about heart disease and obesity in the late 20th century. Though groundbreaking for its time—drawing from early Dietary Guidelines and aiming to simplify calorie balance—it drew fire for overhyping carbs (and therefore fueling low-fat diet trends at the time), underemphasizing healthy fats, lacking portion-size clarity, and inadvertently promoting oversized servings of pasta and bread that clashed with emerging science on glycemic load and metabolic health.

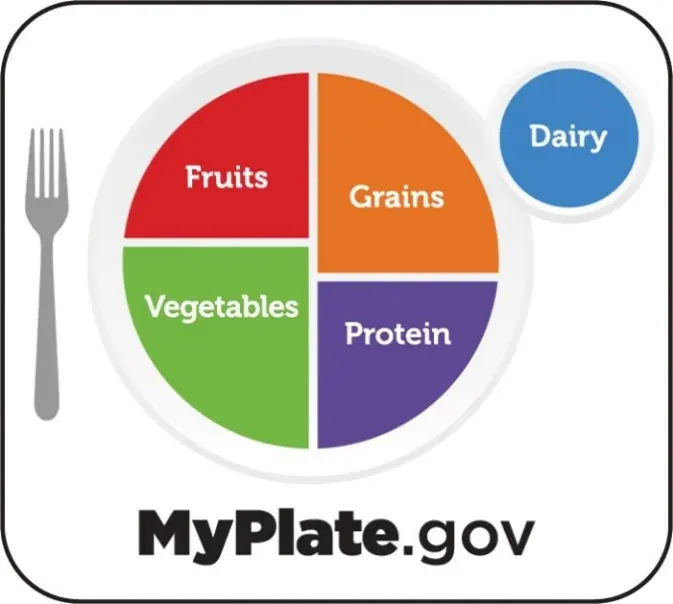

In 2011, the USDA made a bold shift in how America visualizes healthy eating by retiring the iconic 1992 Food Guide Pyramid, which had guided nutrition advice for nearly two decades, and introducing MyPlate—a simple, colorful plate icon meant to cut through confusion and align with evolving nutrition science. The pyramid, with its tiered structure resembling a food hierarchy, had been criticized for being too abstract, promoting excessive grain intake (6-11 servings per day at the broad base, often including refined carbs), and failing to emphasize portion sizes or food quality in a way that resonated with busy families. MyPlate emerged as a response to these shortcomings, aiming to make balanced eating as straightforward as looking at your dinner plate, and was backed by updated Dietary Guidelines that reflected more substantial evidence for plant-forward diets and moderation of carbs.

MyPlate’s core visual was deceptively simple: a divided plate where fruits and vegetables occupy half the space (urging “make half your plate fruits and vegetables”), grains take up one-quarter (with a call to choose at least half as whole grains like brown rice or oats), proteins fill the other quarter (from lean meats, poultry, fish, beans, eggs, or nuts), and a small side glass represents dairy (or fortified alternatives like soy milk). This design promoted portion control through visual proportions—no need for complex serving calculations—while spotlighting variety within groups, such as colorful produce for nutrients and diverse proteins for completeness. Additional principles included balancing calories with physical activity, cutting back on added sugars, saturated fats, and sodium, and personalizing intake based on age, sex, and activity level via online tools, making it more actionable for real-life meals.

Compared to the pyramid’s carb-heavy base and vague moderation at the top (fats, oils, and sweets “sparingly”), MyPlate flipped the script toward balance and practicality, elevating vegetables and fruits, dialing back grains, and integrating dairy more visibly without letting it dominate. This change better aligned with research showing the benefits of higher plant intake, moderate protein, and limited refined carbs for preventing obesity, diabetes, and heart disease, while ditching the pyramid’s misleading “eat more from the bottom” vibe that had fueled oversized pasta bowls and bagel binges. Though still not perfect—critics noted it underplayed healthy fats and water—MyPlate marked a user-friendly evolution, setting the stage for future refinements, such as the 2026 Real Food Pyramid.

Differences with the 2026 Real Food Pyramid

Earlier USDA tools—like the 1992 Food Guide Pyramid, and the later MyPlate graphic—focused on proportions of food groups but were less explicit about food processing and protein quantity or quality. They typically emphasized grains (including many refined grain products) as the base, with general guidance on variety and moderation rather than strong language about ultra-processed foods.

Significant departures in 2026 include:

- Processing focus: The new pyramid elevates “whole, nutrient-dense, naturally occurring” foods and directly calls out the dangers of highly processed foods, something previous visual guides did not do as clearly.

- Protein prominence: Instead of placing grains at the base, the real food pyramid places high-quality protein, dairy, and healthy fats at the foundation and sets a specific protein target of 1.2–1.6 grams per kilogram of body weight per day, which is higher and more specific than older guidance.

- Refined carb downgrade: Refined carbohydrates are explicitly discouraged, with a clear distinction between whole grains and processed carb products; older pyramids and MyPlate often visually grouped refined and whole grains together.

- Metabolic framing: The new framework is framed as a response to epidemics of prediabetes, diabetes, obesity, and chronic disease, linking these to the prior era of guidance that did not adequately restrict ultra-processed foods.

From a messaging standpoint, the new pyramid is more aligned with low-processing, higher-protein, fiber-rich, and healthy-fat dietary patterns that are also seen in many anti-inflammatory and Mediterranean-style diets, even though it stops short of prescribing one named dietary pattern.

The 2026 Real Food pyramid, launched amid high expectations for a nutrition reset, has also ignited debate among designers, dietitians, public health advocates, and scientists who see it as a step backward in clarity, science, and equity.

Visually, the pyramid’s inverted design—wide at the top, with protein, dairy, and fats dominating the space, while whole grains shrink to a narrow peak—fundamentally confuses viewers about portion priorities, evoking the very pyramid format the USDA abandoned in 2011 as too abstract and misleading. Designers point to cluttered, mismatched icons like a whole chicken carcass (implying oversized servings), avocados next to butter, and vague “real food” labels that fail to specify practical amounts or definitions, making it harder for families to translate into grocery lists or meals compared to MyPlate’s straightforward plate visual. This retro aesthetic feels politically nostalgic rather than user-centered, alienating non-experts and undermining the goal of intuitive public guidance.

On the science front, nutritionists point to inconsistencies that they claim erode public trust. For example, the pyramid glorifies meats, full-fat dairy, and even saturated fats like butter and beef tallow at its expansive base, yet the accompanying text caps saturated fat at under 10% of calories, without reconciling how a steak-and-cream-heavy diet achieves this. The aggressive protein push of 1.2 to 1.6 grams per kilogram body weight daily ignores data showing most Americans already exceed protein needs, risks kidney strain in some populations, and sidelines fiber superstars like beans, lentils, and chickpeas that could balance the plate without excess calories. Other contradictions abound: it endorses liberal salting for flavor while urging sodium reduction, offers fuzzy alcohol messaging (neither banning nor promoting it clearly), and skimps on plant diversity, with little mention of soy, beans, or culturally relevant proteins beyond mainstream animal sources. Critics argue this reflects “protein hype” over balanced evidence, potentially worsening metabolic issues, rather than resolving the obesity and diabetes epidemics it claims to target.

Other concerns focus on the pyramid’s origins and fallout. For example, the process sidelined the independent Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, dismissing over half its peer-reviewed recommendations in favor of appointees with documented ties to the meat, dairy, and supplement industries, raising red flags about corporate capture of impartial science. This could ripple into federal programs like school lunches and WIC, prioritizing pricier animal proteins over affordable plants and exacerbating food insecurity for low-income families.

Environmentally, the meat-centric emphasis clashes with climate science, as beef and dairy production drive emissions, while equity gaps loom large—vegan, vegetarian, or culturally diverse eaters find little accommodation, and global health patterns like Mediterranean or Asian diets get overshadowed.

Heart experts warn that the saturated fat elevation contradicts landmark studies linking it to cardiovascular disease, potentially reversing decades of progress on cholesterol management.

While the pyramid earns praise for finally “naming and shaming” ultra-processed foods—a long-overdue nod to their role in chronic illness—its execution, industry fingerprints, and visual misfires have made it divisive, prompting calls for swift revisions to reclaim more evidence-based credibility.

<h2 id="thyroid">Implications for Hashimoto’s, hypothyroidism, and thyroid health</h2>

For people with Hashimoto’s or hypothyroidism, diet is not a replacement for appropriate thyroid hormone replacement, but nutrition can significantly influence inflammation, weight, metabolic health, and your quality of life. The Real Food Pyramid can be adapted into a thyroid-supportive framework by emphasizing three pillars: anti-inflammatory foods, metabolic stability, and critical micronutrients.

Potential benefits

Several aspects of the 2026 pyramid align with evidence-informed dietary strategies for people with autoimmune Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and hypothyroidism:

- Higher protein, stable blood sugar: A protein target of 1.2 to 1.6 g/kg/day can help preserve lean mass, support feelings of fullness, stabilize your blood sugar, and assist weight management—key issues for many hypothyroid patients.

- Whole, minimally processed plant foods: The emphasis on whole vegetables, fruits, and whole grains increases intake of fiber, antioxidants, and polyphenols, which can modulate inflammation and the gut microbiota implicated in autoimmunity.

- Healthy fats: Encouraging fats from fish, nuts, seeds, olives, and avocados -- as well as anti-inflammatory oils -- helps raise omega-3 intake and monounsaturated fats, both supportive of anti-inflammatory dietary patterns and associated with improvements in autoimmune and cardiometabolic markers in Mediterranean-style diets.

Clinical and mechanistic data suggest that anti-inflammatory, Mediterranean-style approaches can reduce oxidative stress and may improve disease activity scores, body composition, and antibody levels in Hashimoto’s and hypothyroidism, particularly when combined with strategies such as gluten reduction for some individuals. The Real Food Pyramid’s focus on minimally processed, plant-forward meals with healthy fats aligns with this pattern.

Where Hashimoto’s and hypothyroid patients may need personalization

Despite its advantages, people with Hashimoto’s often need more specific guidance than the general real-food pyramid provides. Important considerations include:

- Gluten and grains: Some studies suggest that a gluten-free or Mediterranean-gluten-free pattern can reduce thyroid antibodies and inflammation in subsets of patients, particularly those with celiac disease or non-celiac gluten sensitivity. The pyramid encourages whole grains but does not distinguish between gluten-containing and gluten-free options; many patients may do best by emphasizing gluten-free whole grains like quinoa, buckwheat, and rice.

- Goitrogenic vegetables: Cruciferous vegetables are rich in beneficial phytochemicals but can, in very high raw amounts, interfere with iodine handling; cooking largely mitigates this, and moderate intakes of cooked crucifers are generally considered safe. The Real Food Pyramid’s broad vegetable emphasis works well as long as patients include cooked crucifers and overall adequate iodine and selenium intake from diet or supplements guided by their clinicians.

- Dairy tolerance: Full-fat dairy is encouraged in the protein and healthy fat tier, but many with Hashimoto’s report lactose intolerance or sensitivity to specific dairy proteins. In those cases, switching to lactose-free or dairy-free options while still meeting protein and calcium targets is appropriate.

- Ultra-processed “gluten-free” and “diet” products: While the pyramid warns against highly processed foods, thyroid patients trying to “eat healthy” may still gravitate toward processed gluten-free breads, bars, and low-calorie snacks that undermine blood-sugar stability and gut health; emphasizing truly whole foods is critical.

Autoimmune-specific approaches like the Autoimmune Protocol (AIP) diet can improve quality of life but are more restrictive; they are not reflected in the general pyramid and are typically used short-term with structured reintroduction. The 2026 guidelines are best viewed as a flexible, less restrictive baseline that thyroid patients can modify with help from a clinician or nutritionist.

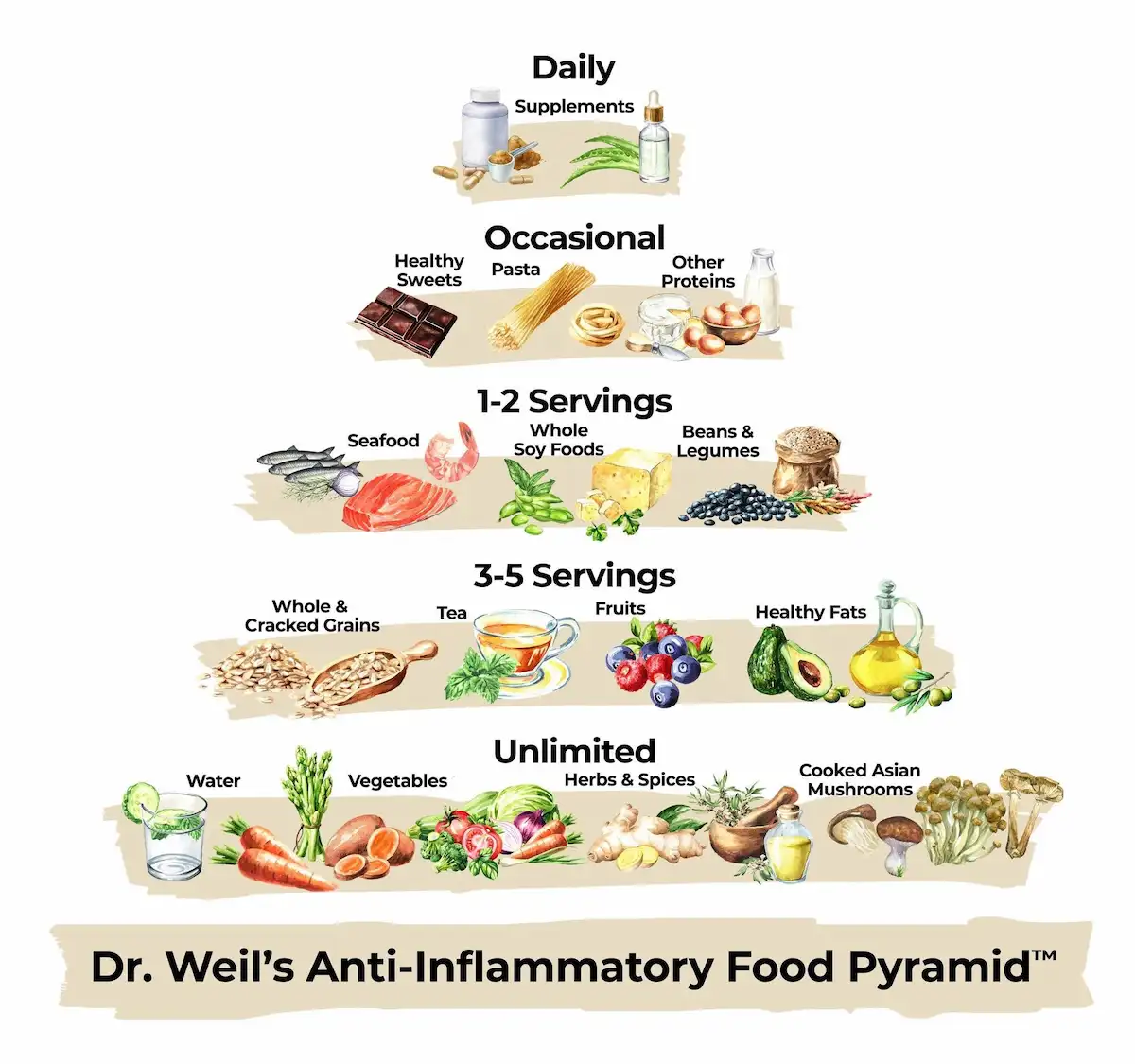

Andrew Weil, MD, is a Harvard-trained physician, author, and pioneer of integrative and functional medicine, best known for blending conventional medical science with nutrition, lifestyle, and mind–body approaches to promote long-term health and reduce chronic inflammation. In 2025, Dr. Weil introduced his Anti-Inflammatory Food Pyramid, which was explicitly designed to reduce chronic, low-grade, and systemic inflammation through a Mediterranean-like, plant-forward diet. Rather than organizing foods strictly by macronutrient categories, it layers foods from the base upward according to how much and how often they should be eaten.

Key structural elements include:

- Base: Water throughout the day, plus generous vegetables (4–5+ servings) and fruits (3–4 servings) rich in flavonoids, carotenoids, and fiber.

- Starches and legumes: Whole and cracked grains (3–5 servings per day) and beans/legumes (1–2 servings per day) as low-glycemic, fiber-rich carbohydrate sources.

- Healthy fats and omega-3s: Multiple daily servings of healthy fats (olive oil, nuts, seeds, avocados, omega-3-rich foods), and regular fish and shellfish (2–6 servings per week) as anti-inflammatory fat sources.

- Soy, mushrooms, and other proteins: Whole-soy foods (1–2 servings/day), cooked Asian mushrooms, modest amounts of high-quality dairy, eggs, and poultry/lean meat (1–2 servings/week), plus herbs, spices, and teas with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties.

- Top of the pyramid: Healthy sweets, small amounts of dark chocolate, and optional red wine in moderation.

The pyramid also includes a specific supplement layer (multivitamin/multimineral, omega-3 fish oil, vitamin D3, CoQ10) to address micronutrient gaps, which distinguishes it from USDA-style food guides, which generally do not include supplement recommendations.

Both pyramids share a whole-food emphasis but differ in the level of detail, the explicit anti-inflammatory framing, and the positioning of specific food categories.

Structural and emphasis differences

- Anti-inflammatory vs. “real food”: Dr. Weil’s framework is explicitly anti-inflammatory and is modeled after Mediterranean and Asian traditions, with detailed recommendations for herbs, spices, teas, and polyphenol-rich foods. The Real Food pyramid is framed around chronic disease prevention and the harms of ultra-processing, but is less specific about phytochemical-rich “extras.”

- Protein positioning: The 2026 pyramid puts protein, dairy, and healthy fats at the base and sets a quantitative protein target, effectively making protein the structural center of the diet. Dr. Weil’s pyramid gives more visual and textual weight to vegetables, fruits, and whole grains as the bulk of intake, with animal protein in small to moderate amounts and plant proteins (soy, beans) encouraged regularly.

- Supplements and specific foods: Weil’s pyramid incorporates a supplement layer, guidance on particular teas, mushrooms, soy foods, and dark chocolate, and even mentions optional red wine, while the Real Food pyramid stays at the level of food groups without explicitly mentioning or endorsing alcohol or supplements.

Suitability for Hashimoto’s and hypothyroidism

From a thyroid and autoimmune perspective, Dr. Weil’s pyramid has several strengths:

- High vegetable and fruit intake, a wide variety of colors, and an emphasis on herbs/spices (turmeric, ginger, garlic, etc.) support an anti-inflammatory and antioxidant-rich pattern relevant to autoimmune conditions.

- A strong focus on omega-3 fats (fish, fish oil) and monounsaturated fats (olive oil, nuts, avocados) mirrors dietary patterns shown to reduce oxidative stress and improve clinical outcomes in Hashimoto’s and related autoimmune diseases.

- Regular legumes and whole grains provide fiber to support gut microbiota and metabolic health, which are important in autoimmune regulation. However, some patients may need to avoid gluten or modify their legume intake.

Potential caveats include:

- Gluten and grain choice: Whole and cracked grains are encouraged but not specified as gluten-free; patients with celiac disease, suspected gluten intolerance, or high antibody burdens may benefit from a Mediterranean-style gluten-free adaptation, which has shown favorable effects on antibodies and metabolic parameters.

- Soy and autoimmunity: Whole soy foods are central in Weil’s protein section; soy is generally safe and may have cardiovascular and menopausal benefits, but some thyroid patients prefer limiting soy around the time of thyroid hormone replacement medication, dosing to avoid absorption interference, and may wish to individualize soy intake.

- Red wine and sweets: Optional red wine and “healthy sweets” may suit some, but patients with fatigue, blood sugar instability, or liver concerns may be better served by minimizing alcohol and focusing on whole fruits and minimal amounts of dark chocolate.

In practice, a Hashimoto’s-adapted version of Weil’s pyramid looks very close to a gluten-conscious Mediterranean diet: lots of vegetables and fruits, olive oil and nuts, beans and lentils, regular fish, modest poultry, minimal red and processed meat, and limited sweets and alcohol. This pattern is broadly supported by evidence as beneficial or at least neutral for autoimmune thyroiditis and systemic inflammation.

.webp)

For people with Hashimoto’s and hypothyroidism, both the 2026 Real Food Pyramid and Dr. Weil’s Anti-Inflammatory Pyramid point toward the same core truth: mainly eating whole, minimally processed foods with adequate protein, plenty of plants, and healthy fats is one of the most powerful ways to support thyroid, metabolic, and overall health over the long term.

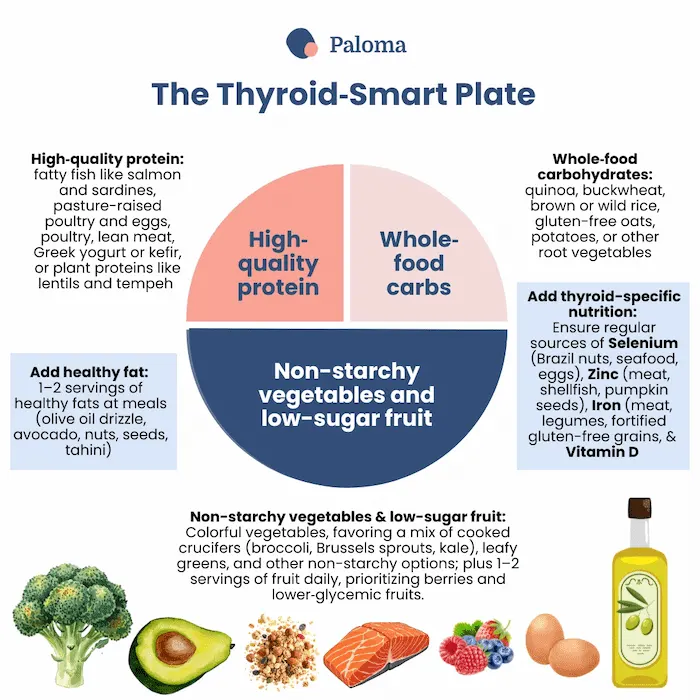

1. Build a thyroid-smart plate template

Use a simple plate visual you can repeat at most meals:

- ¼ plate: High-quality protein (fatty fish like salmon and sardines, pasture-raised poultry and eggs, poultry, lean meat, Greek yogurt or kefir, or plant proteins like lentils and tempeh if tolerated), working toward at least ~1.2 g/kg/day total protein intake, and up to 1.6 g/kg/day if you are trying to lose weight or preserve muscle.

- ½ plate: Colorful vegetables, favoring a mix of cooked crucifers (broccoli, Brussels sprouts, kale), leafy greens, and other non-starchy options; add 1–2 servings of fruit daily, prioritizing berries and lower-glycemic fruits.

- ¼ plate: Whole-food carbohydrates (quinoa, buckwheat, brown or wild rice, gluten-free oats, potatoes, or other root vegetables), adjusted up or down based on appetite, blood sugar, and activity.

- Add: 1–2 servings of healthy fats at meals (olive oil drizzle, avocado, nuts, seeds, tahini, fatty fish).

- Ensure regular sources of selenium (Brazil nuts, seafood, eggs), zinc (meat, shellfish, pumpkin seeds), iron (meat, legumes, fortified gluten-free grains), and vitamin D (fatty fish, fortified foods, supplements if needed), as these nutrients are important in thyroid hormone synthesis, conversion, and immune balance.

This template combines the higher-protein focus of the Real Food pyramid with the plant-forward, olive oil-rich emphasis of Dr. Weil’s pyramid.

2. Make protein a daily non-negotiable

Because hypothyroidism is associated with a lower metabolic rate, increased risk of muscle loss (especially with dieting), and blood sugar swings, making protein more central is highly strategic. Aim to:

- Include a meaningful protein source at every meal (e.g., 20–35 g per meal for many adults, adjusted to body size and needs).

- Rotate sources: fatty fish (salmon, sardines, trout), poultry, eggs, Greek yogurt or kefir (if tolerated), tofu or tempeh, and beans/lentils.

- For those who struggle to hit targets with food alone, consider discussing a clean protein powder with your clinician or dietitian.

This aligns with the Real Food pyramid’s explicit protein target and complements Weil’s emphasis on legumes and modest animal protein.

3. Prioritize anti-inflammatory fats

Inflammation is central in autoimmune thyroiditis, and the quality of dietary fat strongly influences inflammatory pathways. To align with both pyramids:

- Use extra-virgin olive oil as your default cooking and salad oil.

- Eat fatty fish at least 2 times per week (salmon, sardines, mackerel, herring), or discuss an omega-3 supplement with your clinician.

- Include a daily handful of nuts and seeds (walnuts, almonds, chia, flax, pumpkin seeds).

- Limit industrial seed-oil-heavy ultra-processed foods (chips, packaged baked goods, fast food) and processed meats.

These steps reflect the anti-inflammatory fat focus in Dr. Weil’s pyramid and the “healthy fats from whole foods” tier in the Real Food pyramid.

4. Choose carbs that love your thyroid (and blood sugar)

Carbohydrates are not the enemy, but the type and amount matter for people with Hashimoto’s, especially when insulin resistance, PCOS, or weight gain are in the picture. Practical moves:

- Make most carbs high-fiber and minimally processed: vegetables, fruits, beans, lentils, and intact or minimally processed whole grains.

- Consider trialing gluten-free whole grains (quinoa, buckwheat, millet, certified gluten-free oats, brown rice), especially if you have celiac disease, positive celiac antibodies, IBS-like symptoms, or stubborn elevations in thyroid antibodies.

- Keep refined carbs (white bread, pastries, sweets, sugary drinks, many “gluten-free junk foods”) for rare occasions; both pyramids agree these should be limited, if used at all.

Observe how your energy, digestion, and brain fog respond over 4–6 weeks when you shift to this style.

5. Get strategic about common thyroid “trigger” foods

Not everyone with Hashimoto’s needs to avoid the same foods, but there are a few categories where it pays to be strategic.

- Gluten: If you have celiac disease or positive celiac antibodies, a strict gluten-free diet is essential. If not, a 6–12 week gluten-reduced or gluten-free trial—while keeping your diet otherwise nutrient-dense—may be worth exploring with your provider.

- Dairy: Full-fat dairy fits easily into the Real Food pyramid, and modest dairy is compatible with Dr. Weil’s approach, but many thyroid patients report digestive or sinus symptoms with cow’s milk products. Consider a 4–6 week trial of lactose-free or dairy-free eating (replacing with fortified plant milks and other calcium sources) and track changes in bloating, mucus, skin, and fatigue.

- Soy: Whole soy foods (tofu, tempeh, edamame) appear in Dr. Weil’s pyramid, and moderate soy is generally safe for most people, but large quantities close to thyroid medication timing may interfere with absorption. If you eat soy, keep it in whole forms, and separate it from your thyroid pill by several hours.

- Goitrogenic vegetables: Crucifers (broccoli, Brussels sprouts, kale) are prominently featured in anti-inflammatory diets; cooking them significantly reduces their goitrogenic potential. For most people, 1–2 servings per day of cooked crucifers within an iodine-adequate diet is safe and beneficial.

The goal is not to restrict everything, but to identify and fine-tune the specific foods that genuinely affect your symptoms or labs.

6. Support key micronutrients

Micronutrient adequacy is a quiet but crucial layer that both pyramids imply – and Dr. Weil’s pyramid makes explicit – through its supplement tier. Discuss testing and individualized supplementation with your clinician for:

- Selenium: Important for thyroid hormone metabolism and antioxidant defense; found in Brazil nuts, seafood, meat, and eggs.

- Vitamin D: Often low in autoimmune conditions; supports immune balance and bone health.

- Zinc and iron: Needed for thyroid hormone synthesis, conversion, and energy; found in meat, shellfish, pumpkin seeds, legumes, and fortified grains.

- B vitamins: Especially B12 and folate, important for energy, mood, and homocysteine metabolism.

A seasonal, nutrient-rich menu should be your primary source, with supplements filling documented gaps, not acting as a substitute for a nutrient-dense diet.

7. Align food timing with thyroid medication

The best eating pattern will be less effective if it interferes with your medication. Common, practical strategies for how and when to take your thyroid medication include:

- Take thyroid hormone replacement medication on an empty stomach with water, typically 30–60 minutes before breakfast or 3–4 hours after your last meal at night (following your prescriber’s instructions).

- Avoid taking it at the same time as high-fiber meals, calcium or iron supplements, or large amounts of soy, as this can reduce absorption.

- Build your breakfast around this timing—e.g., medication upon waking, then a protein-rich breakfast 45–60 minutes later.

Minor timing adjustments can make a noticeable difference in symptom control and lab stability.

8. Monitor, adjust, and get support

Finally, treat this as an evolving experiment rather than a one-time project:

- Track symptoms (fatigue, weight, brain fog, mood, hair, skin, digestion, joint pain) alongside labs (TSH, free T4, free T3 if ordered, antibodies, lipids, glucose/insulin).

- Make one or two changes at a time (e.g., increasing protein and vegetables; then trialing gluten reduction) so you can see what actually helps.

- Consider working with a nutritionist or knowledgeable clinician who understands both thyroid physiology and autoimmune nutrition to help adapt the pyramid frameworks to your life, budget, cooking skills, and cultural food preferences.

The best plan is the one you can live with: consistent, flexible, grounded in real food, and responsive to how your body and labs change over time.

Focus on sustainable patterns over perfection—day after day, prioritize whole foods, quality protein, colorful plants, healthy fats, and far fewer ultra-processed products to nourish your thyroid and body truly. Both the 2026 Real Food pyramid and Dr. Weil’s Anti-Inflammatory pyramid offer useful roadmaps for people with Hashimoto’s and hypothyroidism: one with a high-protein, real-food-first foundation, the other layering in Mediterranean staples like olive oil, legumes, veggies, fruits, and omega-3-rich fish. Personalization is everything—tweaking gluten, dairy, soy, or carbs based on your symptoms, labs, and issues like celiac disease, insulin resistance, or IBS makes all the difference.

At Paloma Health, we go beyond nutrition guidance to deliver comprehensive care tailored just for you: precise thyroid testing, diagnosis, and treatment (including optimized thyroid hormone replacement therapy), perimenopause and menopause support to ease hormonal shifts, gut health strategies to heal from within, and effective weight loss plans that honor your metabolism. Food is a vital complement, never a replacement—our clinicians fine-tune your medication timing, dosing, energy levels, antibodies, and coexisting conditions alongside these real-food patterns, so you thrive holistically.

Are you ready to personalize your path? Consider becoming a Paloma member today!

<div id="schedule_snippet_2" class="max-width _700 doctor-ads"><h1 class="heading-2 hero v2 chechkout-right-copy">Dealing with Hypothyroidism? Video chat with a thyroid doctor</h1><h5 class= “heading-3 centered left leftyer”>Get answers and treatments in minutes without leaving home - anytime. Consult with a U.S. board-certified doctor who only treats hypothyroidism via high-quality video. Insurance accepted.</h5><a href="https://app.palomahealth.com/book-appointment/" target="_blank" class="button spacing orange w-button">Schedule</a></div>

1. What is the 2026 Real Food Pyramid in simple terms?

It is a new U.S. dietary framework that puts whole, minimally processed foods at the center, with three main tiers: protein/dairy/healthy fats at the base, vegetables and fruits in the middle, and whole grains at the top. Its core message is to eat “real food” and minimize ultra-processed products that drive chronic disease.

2. How is the 2026 Real Food Pyramid different from the old USDA pyramid and MyPlate?

Unlike older guides that emphasized grains and were less explicit about processing, the new pyramid: favors higher protein, clearly discourages refined carbohydrates, and directly calls out highly processed foods as harmful. It also provides a specific daily protein target (1.2–1.6 g/kg), unlike older graphics.

3. What is Dr. Weil’s Anti-Inflammatory Food Pyramid?

Renowned integrative physician Dr. Andrew Weil released his Anti-Inflammatory Food Pyramid in 2025. It’s a visual guide to a Mediterranean-style, anti-inflammatory diet built on vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, healthy fats (mainly olive oil and omega-3s), and modest amounts of animal protein. It also highlights herbs, spices, teas, and a small supplement layer (e.g., multivitamin, omega-3, vitamin D).

4. Are these pyramids actually helpful for people with Hashimoto’s and hypothyroidism?

Yes, both can be useful frameworks because they emphasize whole foods, stable blood sugar, anti-inflammatory fats, and plenty of fiber-rich plants, all of which support metabolic and immune health in Hashimoto’s and hypothyroidism. They are not a replacement for thyroid medication but can meaningfully complement medical treatment.

5. Do I need to go gluten-free if I have Hashimoto’s?

Not everyone needs to be fully gluten-free, but those with celiac disease or positive celiac antibodies do. Some others may benefit from a gluten-reduced or gluten-free Mediterranean-style pattern (using gluten-free whole grains) to help with symptoms and possibly antibody levels, ideally guided by a clinician.

6. How much protein should I aim for with Hashimoto’s or hypothyroidism?

The Real Food pyramid suggests 1.2–1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day, which is reasonable for many people with hypothyroidism, especially if they are trying to manage weight and preserve muscle mass. This usually means including a solid protein source at every meal (e.g., 20–35 g per meal for many adults).

7. Are goitrogenic vegetables (like broccoli or kale) a problem

For most people with adequate iodine intake, moderate amounts of cooked cruciferous vegetables are safe and beneficial due to their fiber and phytochemicals. Cooking significantly reduces the goitrogenic compounds in crucifers, so focusing on cooked crucifers rather than large amounts of raw crucifers is a practical approach.

8. Where do dairy and soy fit if I have thyroid issues?

Both pyramids allow dairy and, in Dr. Weil’s case, encourage whole soy foods, but thyroid patients often need personalization. If you notice digestive, sinus, or skin symptoms with dairy, or have concerns about soy or medication absorption, you can trial reductions and separate soy intake by several hours from your thyroid pill, under guidance.

9. How should I handle carbs if I struggle with weight or blood sugar?

Prioritize high-fiber, minimally processed carbs—vegetables, fruits, beans, lentils, and intact whole grains—and minimize refined starches and sweets. Many with Hashimoto’s do best when each meal pairs these carbs with protein and healthy fats to stabilize energy and blood sugar.

10. What is one simple way to start using these pyramids today?

Use a plate model at most meals: half vegetables, one-quarter high-quality protein, one-quarter whole-food carbs, plus a serving or two of healthy fats (like olive oil or nuts). From there, adjust for gluten tolerance, dairy or soy sensitivity, and personal preferences while keeping the focus on real, minimally processed foods.

.webp)

.webp)

%20(1).webp)